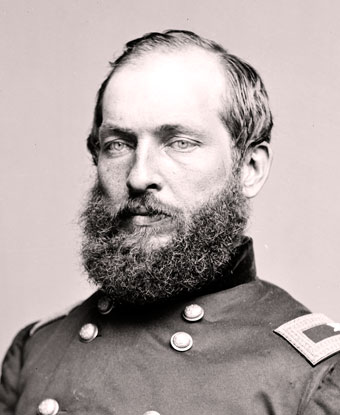

Colonel James Garfield [US]

Commander of the First Kentucky Cavalry during the Mexican War, Marshall was much revered for his military sagacity. In November, 1861, he traveled to Wytheville, Virginia, accepted the Brigadier General’s commission offered him by President Jefferson Davis, and took command of the Army of Southwestern Virginia. His brigade was made up of natives of Southwestern Virginia and Eastern Kentucky. Wythe County’s 29th Virginia Infantry and Wise County’s 54th Virginia Infantry had been strengthened by Captain Jeffress’ artillery battery from Nottaway County, Virginia.

Marshall and his men set out for Kentucky in late December, 1861, and when they reached Pound Gap, they were reinforced by Colonel John S. Williams’ 5th Kentucky Infantry, which was still licking the wounds it had received during the Battle of Ivy Mountain. Williams’ men had established a Winter Camp at Pound Gap following their retreat from Pikeville on November 8th.

With the 5th Kentucky leading the way, Marshall’s men marched down the Big Sandy Valley and established a fortified camp at Hager Hill in Johnson County and a cavalry camp at the mouth of Jenny’s Creek, near Paintsville.

When word reached Union headquarters in Louisville that the Confederates had reoccupied Eastern Kentucky, Don Carlos Buell, Commander of the Army of the Ohio, contacted Colonel James A. Garfield and gave him the mission of driving them back into Virginia. Garfield was given command of the 18th Brigade, numbering approximately 1,500 men.

Garfield ordered one of his regiments, the 40th Ohio Infantry, to march from Lexington to Prestonsburg and cut off the Confederate line of retreat, and he ordered the 42nd Ohio Infantry and the 14th and 22nd Kentucky Infantries to proceed up the Big Sandy Valley from their base at Catlettsburg. At Louisa they were joined by the 1st Ohio, the 1st Kentucky, and the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry regiments. With Garfield leading the way, the brigade then advanced slowly over muddy roads towards Paintsville.

Near Paintsville, on January 7th, the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry surprised the Confederate cavalry as they were breaking camp at the mouth of Jenny’s Creek. They initially routed them but were bloodied after their pursuit ended in am ambush. Garfield advanced on Hager Hill, only to find that the Confederates had abandoned it. When Garfield’s message to Colonel Cranor, who was advancing from Salyersville, was intercepted, he ordered Cranor and his regiment, the 40th Ohio, to join him at Paintsville.

Meanwhile...

Meanwhile, Marshall was moving south to the Forks of Middle Creek. There he could avoid the planned entrapment and guard his supply line and line of retreat into Virginia.

The Middle Creek valley provided excellent defensive positions for the Confederates, who were poorly armed and equipped, not to mention cold and hungry. On his right wing, along the ridge overlooking the creek, Marshall placed the 29th Virginia and the 5th Kentucky. He posted Jeffress’ artillery battery in the center, next to his command post, so it could sweep the plain. The 54th Virginia he stationed on the hill behind the battery, keeping it in reserve. He stationed his two best cavalry companies, dismounted and commanded by Captains Clay and Thomas, on a low ridge running to his left. Cavalry companies commanded by Cameron, Holliday, Shawhan, and Stone were held in reserve on his immediate right.

At about 1 pm on January 10th, Garfield’s skirmishers encountered Marshall’s pickets, which he had placed about a half-mile upstream from the mouth of Middle Creek. Unsure of Marshall’s position, Garfield ordered a squad of twenty cavalrymen to dash into the valley and draw fire. This ploy sprung Marshall’s trap. A volley from Clay’s and Thomas’ cavalry companies revealed the Confederate position. Seeing this, Garfield ordered his troops to come forward and begin deploying.

After ascending Graveyard Point, which provided him with an excellent view of the Confederate position, Garfield ordered the 40th and 42nd Ohio to cross the swollen creek and attack the Confederate line on the hills bordering the south side of the creek. With his Ohio regiments drawing heavy fire, he then ordered the 14th Kentucky and the 22nd Kentucky to assault the Confederate position on his immediate left, held by Colonel John S. Williams’ 5th Kentucky Infantry.

Here disaster almost overtook the Kentucky Unionists. Since they wore sky-blue jackets, the men of the 14th were initially mistaken for rebels by their Ohio comrades. Only quick thinking by Garfield and a ‘Hurrah for the Union, –which the Confederates promptly answered with ‘Hurrah for Jeff Davis, –saved the Kentuckians from sustaining heavy casualties.

The piecemeal Union attack slowly forced the Confederates up the steep hill. At 5 pm, with the sun sinking below the horizon, the fighting petered out. Marshall, fearing that his hungry men would desert him in droves if they remained in their present position, decided to burn his heavier wagons and retreat southward, using the left fork of the creek as his escape route. He knew that food for his men and forage for his horses could be obtained at the Joseph Gearhart Farm near modern-day Hueysville.

Having been reinforced by Cranor’s 40th Ohio, Garfield chose to remain on the battlefield. After his burial details had buried the ten Confederates Marshall decided to leave behind, he withdrew to Prestonsburg, where he commandeered a house owned by Prestonsburg lawyer John M. Burns and made it his temporary headquarters.

Garfield’s victory at Middle Creek earned him a promotion to Brigadier General. The problems which Marshall experienced during the campaign caused Confederate authorities to question his ability as a military commander. Marshall’s difficulties also demonstrated that the long supply line which the campaign required, extending over the mountains from Virginia, made it impossible for the Confederates to hold a position in Eastern Kentucky for more than a few weeks.

For his part, Garfield demonstrated that the Big Sandy River could be used to concentrate men and material against any threat mounted by the Confederates from Southwestern Virginia. Although the Big Sandy Valley remained a no-man’s-land for the remainder of the war, the Confederates never regained the advantage which they surrendered as a result of the Battle of Middle Creek.